Current Saskatchewan Public Opinion on Small Modular Nuclear Reactors

Quinn Rozwadowski | University of Saskatchewan | qjr799@usask.ca

Margot Hurlbert | Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy | margot.hurlbert@uregina.ca

Jeremy Rayner | Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy | jeremy.rayner@usask.ca

Loleen Berdahl | Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy | loleen.berdahl@usask.ca

August 30, 2021

Currently, Saskatchewan’s energy infrastructure is highly dependent on coal-fired power plants. Although Saskatchewan was a signatory of the 2016 Vancouver Declaration on Clean Growth and Climate Change, contributing to SaskPower’s decision to set an objective of generating 50% of all electricity from non greenhouse gas-emitting sources by 2030, the Wall government joined a small number of other provinces in rejecting the subsequent federal climate framework that incorporates a carbon tax as the key policy instrument to reduce emissions. Instead, the province developed its own approach to climate policy, published as “Prairie Resilience,” which emphasizes rapid emissions reductions through the adoption of low emissions technologies in sectors such as electricity production. While power generation by natural gas offers a degree of immediate improvement, and the province is poised to continue to move in this direction in the short-term, replacing the combustion of coal with gas will not meet long-term zero-emissions targets. Renewable energy sources such as wind, solar, and geothermal will provide some of the necessary capacity, as will the recently announced contract to purchase more hydro power from Manitoba, but a sizable gap remains to be filled.

Nevertheless, many observers were surprised when Prairie Resilience mentioned nuclear power as an option to generate emissions-free electricity and the province subsequently underlined its nuclear ambitions by joining Ontario and New Brunswick (and later Alberta) in agreeing to work together to develop and deploy a new generation of nuclear reactors. Saskatchewan has extensive high-quality uranium deposits and uranium mining forms a major part of the provincial economy. Despite this, nuclear power generation has long been inhibited by the feasibility of large contemporary reactors and by sharply divided public opinion toward them. The development of small modular reactors (SMRs) promises to effectively address the cost and safety concerns of nuclear power, leaving uncertain public support as the most substantial barrier to their use.

Will the Saskatchewan public support a move toward nuclear energy in the form of SMRs? In this research brief, we present Saskatchewan public opinion on the use of SMRs. Drawing upon data from two large-N surveys of Saskatchewan’s general populace, the October 2020 C-Dem Saskatchewan Election Study and the March 2021 Viewpoint Saskatchewan survey, we demonstrate that nuclear power generation in the form of SMRs enjoys consistent support across much of the province’s population. At the same time, we note that a significant proportion of respondents, particularly women, remain uncertain or undecided on the issue, suggesting that the issue could quickly become polarized again and there is a need for continued public engagement.

Background

Nuclear power has traditionally been a divisive issue in Canada, as a non-emitting and cost-effective power source frequently criticized by detractors as posing environmental contamination and public security risks. In the mid-1970s, public hearings led to an official recommendation that Saskatchewan expand its uranium production but not develop nuclear power generation capabilities (i). More recently, Brad Wall’s Saskatchewan Party government established a Uranium Development Partnership. Its report, released in 2009, was followed by the report summarizing the results of intensive public consultations (conducted by Dan Perrins) and the report of a Standing Committee of the Provincial Legislature that was tasked with determining how to best meet Saskatchewan’s future energy needs. Together, these reports led Energy and Resources Minister Bill Boyd to state the government had “received the most comprehensive overview of the uranium industry in our province’s history.” While uranium mining and nuclear research received extensive support, the government was discouraged from implementing a proposal to build Saskatchewan’s first nuclear power plant. Notably, small nuclear generation was not publicly rejected (ii).

Canadian attitudes towards nuclear power have been becoming more positive over time. In 2012, the Canadian Nuclear Association’s longitudinal National Nuclear Attitudes Survey found nuclear power generation was the least supported source of electricity at a mere 37% nationwide, with the majority of Canadians seeing it as “expensive” and “dangerous” (iii). Eight years later, a 2020 Abacus Data report released by the CNA revealed that 55% of Canadians now supported wider use of nuclear power generation, with only 10% somewhat or strongly opposed to it. This substantial shift was associated with increasingly significant and widespread concern about carbon emissions and climate change, and slowly increasing knowledge and understanding of nuclear power technology and safety (iv).

Other recent research suggests this trend towards widespread positive public opinion on nuclear power generation may be prevalent in Saskatchewan. A 2014 Saskatchewan Nuclear Attitudes study released by the Nuclear Policy Research Initiative at the University of Saskatchewan found roughly half of respondents reported a positive impression of nuclear power while two thirds of respondents indicated support for Saskatchewan using nuclear power in the future (v). More recently, in a 2019 telephone survey of 1,014 Saskatchewan residents, SMRs ranked behind solar, hydro, natural gas, wind, and geothermal in pure preference. When asked to choose a power source to provide safe, reliable, and cost-efficient electricity for the future, however, SMRs ranked behind only natural gas and solar (vi).

Current Saskatchewan Opinion on Small Modular Reactors

Two large studies in 2020 and 2021 show rising public support for nuclear power, at least in the form of SMRs. In October 2020, a majority of respondents expressed that they “strongly agreed” (20.0%) or “somewhat agreed” (33.7%) with the statement that Saskatchewan should use small modular reactors to replace coal energy generation on the provincial electrical grid, while only 15.8% of respondents indicated disagreement. In a second survey in March 2021, the majority of respondents expressed that they “strongly agreed” (19.7%) or “somewhat agreed” (31.8%) with the same statement, while a mere 13.5% strongly or somewhat opposed it (Figure 1). All respondents provided an opinion in October 2020; 144 answered “don’t know” in March 2021.

Figure 1: Opinion on SMRs replacing coal energy generation

Source: C-Dem Saskatchewan Election Study 2020 (N =1003). Viewpoint Saskatchewan Survey 2021 (N = 656). Weighted data. Figures correspond to respondents’ answers to the statement: “Saskatchewan should use small modular reactors to replace coal energy generation on the provincial electrical grid.”

Similar attitudes are seen in response to the statement that Saskatchewan should use small modular reactors for energy generation in remote communities. In October 2020, the majority of respondents expressed that they “strongly agreed” (21.2%) or “somewhat agreed” (34.5%) with that idea, while only 13.6% of respondents indicated disagreement. This sentiment remained largely consistent in March 2021, when a majority of respondents expressed that they “strongly agreed” (23.4%) or “somewhat agreed” (32.2%) with the same statement, while 10.4% strongly or somewhat opposed it (Figure 2). All respondents provided an opinion in October 2020; 140 individuals answered the question with “don’t know” in March 2021.

Figure 2: Opinion on SMRs generating energy for remote communities

Source: C-Dem Saskatchewan Election Study 2020 (N = 1003). Viewpoint Saskatchewan Survey 2021 (N = 660). Weighted data. Figures correspond to respondents’ answers to the statement: “Saskatchewan should use small modular reactors for generation in remote communities.”

Demographics of Public Support for Small Modular Reactors

To what extent does public opinion about SMRs vary across demographic groups? The data suggest only minor differences in support for SMRs between different age groups, education levels, and social classes, while male respondents demonstrate notably greater support for the use of SMRs than do female respondents.

In both the 2020 and the 2021 surveys, greater age is weakly positively associated with both greater support for SMRs replacing coal energy generation (see Table 1) and greater support for SMRs generating electricity for remote communities.

Source: C-Dem Saskatchewan Election Study 2020 (N=1003, p<0.001). Viewpoint Saskatchewan Survey 2021 (N=659, p<0.001). Weighted data. Figures correspond to the respondents’ answers to the statements: “Saskatchewan should use small modular reactors to replace coal energy generation on the provincial electrical grid,” and “What is your age?”

The data from both surveys further illustrate how opinion of SMRs is also largely consistent over different levels of education. Greater education is weakly positively associated with greater support for SMRs replacing coal energy generation (see Table 2) and very weakly positively associated with greater support for SMRs generating energy for remote areas. Notably, across the two measures of support for SMRs and the two surveys on which they were featured, the percentage of respondents indicating support for SMRs was more than two times greater than the percentage indicating opposition within each education level.

Public support for the use of Small Modular Reactors in Saskatchewan

is much greater than opposition, and this overall trend remains

consistently true across common demographic variables.

Source: C-Dem Saskatchewan Election Study 2020 (N=1003, p<0.001). Viewpoint Saskatchewan Survey 2021 (N=657, p<0.015). Weighted data. Figures correspond to the respondents’ answers to the statements: “Saskatchewan should use small modular reactors to replace coal energy generation on the provincial electrical grid,” and, “What is the highest level of education you have completed or the highest degree you have received?”

The March 2021 survey further asked respondents to self-identify their social class. Higher socioeconomic status was weakly positively associated with both greater support for SMRs replacing coal energy generation and generating energy for remote communities (Table 3).

Source: Viewpoint Saskatchewan Survey 2021. Weighted data. Figures correspond to the respondents’ answers to the statements: “Saskatchewan should use small modular reactors to replace coal energy generation on the provincial electrical grid” (N=647, p<0.001) or “Saskatchewan should use small modular reactors for generation in remote communities” (N=653, p<0.001) and “How would you identify your social class?”

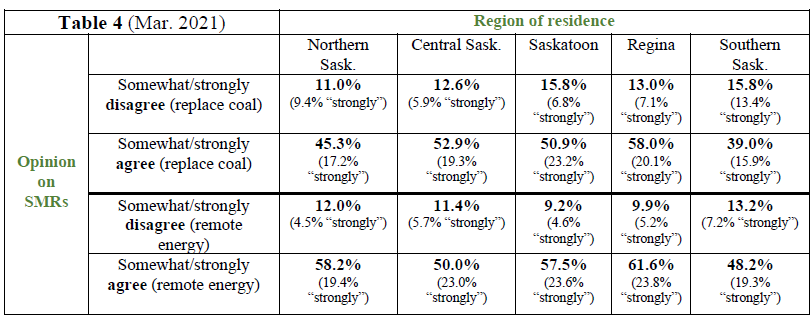

The March 2021 survey also allowed us to consider place of residence, as the respondents’ postal code information was used to construct a set of five broad regional locations. We found that attitudes about the use of SMRs vary moderately across the province, in contrast with the very high level of consistency found to exist across the other demographic measures presented above. While support consistently outweighs opposition, agreement with the use of SMRs to replace coal energy was noticeably lower in South Saskatchewan, while support for SMRs generating electricity for remote areas of the province was especially high in North Saskatchewan and in the major population centres of Saskatoon and Regina (Table 4).

Source: Viewpoint Saskatchewan Survey 2021. Weighted data. Figures correspond to the respondents’ answers to the statements: “Saskatchewan should use small modular reactors to replace coal energy generation on the provincial electrical grid” (N=611) or “Saskatchewan should use small modular reactors for generation in remote communities” (N=618) and “What is the postal code of your residence?”

In both surveys, gender is the most important determinant of attitudes toward the adoption of SMRs in Saskatchewan, with men indicating support more often and being more likely to hold strong positive attitudes about SMRs than women (Table 5). (Due to the very low numbers of respondents who selected a gender other than “woman” or “man,” these alternative responses were removed from the statistical analysis.)

Source (replace coal): C-Dem Saskatchewan Election Study 2020 (N=991, p<0.001). Viewpoint Saskatchewan Survey 2021 (N=641, p<0.001). Weighted data. Figures correspond to respondents’ answers to the statements: “Saskatchewan should use small modular reactors to replace coal energy generation on the provincial electrical grid,” and “What is your gender?”

Source (remote energy): C-Dem Saskatchewan Election Study 2020 (N=990, p<0.001). Viewpoint Saskatchewan Survey 2021 (N=647, p<0.001). Weighted data. Figures correspond to respondents’ answers to the statements: “Saskatchewan should use small modular reactors for generation in remote communities,” and “What is your gender?”

Political Factors and Public Support for Small Modular Reactors

To what extent does public opinion about SMRs vary with political factors? As with the majority of the demographic variables, there are only relatively minor variations in support for SMRs with regard to self identified political ideology and provincial voting intentions. However, respondents who indicated greater levels of political interest tended to be noticeably more agreeable to the adoption of SMRs.

In the October 2020 survey, respondents were asked to place their self-identified political ideology on a scale from “left-wing” to “right-wing.” (We grouped responses as follows: a value of 0-3 was classified as “left-wing,” a value of 4-6 was classified as “centrist,” and a value of 7-10 was classified as “right-wing.”) We found that those with more “right-wing” political beliefs are somewhat more likely to have greater support for SMRs. However, an identical question was posed in the March 2021 survey, and the opposite pattern was found, to the same marginal degree. The contrasting data between the two surveys suggest no major ideology-based split on support for SMRs exists, but rather that “right-wing” respondents tend to have stronger opinions (Figure 7).

It is relevant to note here that a particular continuation of this trend, among individuals with “right-wing” political beliefs, may signal change for Saskatchewan’s current government. Support for SMRs by the conservative Sask. Party stands contrary to party leader Premier Scott Moe’s historic practice of opposing policies advocated by the federal government, but is evidently favoured by right-wing survey respondents.

Figure 7: Opinion on SMRs by Political Ideology

Source: C-Dem Saskatchewan Election Study 2020 (N=982, p<0.001). Viewpoint Saskatchewan Survey 2021 (N=656, p<0.001). Weighted data. Figures correspond to the respondents’ answers to the statements: “Saskatchewan should use small modular reactors to replace coal energy generation on the provincial electrical grid” or “Saskatchewan should use small modular reactors for generation in remote communities” and “Where would you place yourself on a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 means very left-wing, and 10 means very right-wing?”

The surveys also suggest that agreement with the use of SMRs in Saskatchewan is quite consistent across supporters of different political parties. In October 2020, respondents were asked to identify which provincial party they typically supported; in March 2021, the survey asked which party respondents would vote for if a provincial election occurred. As Tables 5 and 6 show, the degree to which agreement with the implementation of SMRs outweighed disagreement was relatively consistent across various provincial voting inclinations.

Source: C-Dem Saskatchewan Election Study 2020 (N=995, p<0.001). Viewpoint Saskatchewan Survey 2021 (N=659, p<0.001). Weighted data. Figures correspond to the respondents’ answers to the statements: “Saskatchewan should use SMRs to replace coal energy generation on the provincial electrical grid,” and “In provincial politics, do you usually think of yourself as a…” or “If a Saskatchewan provincial election was held today, which party would you vote for?”

Source: C-Dem SK Election Study 2020 (N=992, p<0.001). Viewpoint SK Survey 2021 (N=619, p<0.001). Weighted data. Figures correspond to the respondents’ answers to the statements: “Saskatchewan should use small modular reactors for generation in remote communities,” and “In provincial politics, do you usually think of yourself as a…” or “If a provincial election was held today, which party would you vote for?”

The October 2020 survey also asked respondents to place their self-identified political interest on a 0-10 scale. (We grouped the responses as follows: a value of 0-3 was classified as “low interest,” a value of 4-6 was classified as “moderate interest,” and a value of 7-10 was classified as “high interest.”) We found that a moderate positive relationship existed between higher interest in politics and greater support for SMRs, driven by those with lower levels of political interest being much more likely to “neither agree nor disagree” (Table 7).

Source: C-Dem Saskatchewan Election Study 2020. Weighted data. Figures correspond to the respondents’ answers to the statements: “Saskatchewan should use small modular reactors to replace coal energy generation on the provincial electrical grid” (N=1001, p<0.001) or “Saskatchewan should use small modular reactors for generation in remote communities” (N=999, p<0.001) and “How interested are you in politics generally?”

Issue-Specific Attitudinal Factors of Support for Small Modular Reactors

Are attitudes towards SMRs associated with broader public attitudes on fossil fuels and the environment? The surveys suggest that increased agreement with the use of SMRs is only weakly associated with both greater support for a sustainable oil and gas sector (Table 8) and for provincial environmental spending (Table 9).

Source: C-Dem Saskatchewan Election Study 2020 (N=1000, p<0.001). Viewpoint Saskatchewan Survey 2021 (N=650, p<0.001). Weighted data. Figures correspond to the respondents’ answers to the statements: “Saskatchewan should use small modular reactors to replace coal energy generation on the provincial electrical grid,” and “Canada’s economic future should include a sustainable oil and gas sector.”

Source: C-Dem Saskatchewan Election Study 2020. Weighted data. Figures correspond to the respondents’ answers to the statements: “Saskatchewan should use small modular reactors to replace coal energy on the provincial electrical grid” (N=1001, p<0.001) or “Saskatchewan should use small modular reactors for generation in remote communities” (N=1000, p<0.001) and “How much should the provincial government spend on the environment?”

Concluding Thoughts

At present, public support for the use of SMRs in Saskatchewan is much greater than opposition, with strong positive opinion outweighing strong negative opinion by a factor of three. Notably, this trend is roughly consistent across various physical and geographic demographics, political ideologies and voting behaviours, and degrees of support for fossil fuels and environmental spending. Nevertheless, a significant group of respondents held no strong opinion on the issue and, in some demographics, this group has increased in number between the two surveys. Given the lack of directly comparable longitudinal data from previous years it is unclear whether this group is predominantly made up of those who were previously opposed but are now more open to the implementation of SMRs in Saskatchewan, those who have simply not paid sufficient attention to the issue to form an opinion and could therefore drastically alter the picture of public support in the near future, or even those previously in favour of SMRs who have now developed doubts. Regardless, any significant shift in attitude by a portion of this large group could change the complexion of the debate entirely. Altogether, the data support three general conclusions: nuclear power is currently not an untouchably polarized issue; exploring SMRs is a viable – even advisable – policy choice for any Saskatchewan government; and further work must be done with regard to public engagement and education on the matter of modern nuclear technology.

When drawing these conclusions, it is important to note the framing of the survey questions and their potential impacts. The question relating to the implementation of SMRs on the provincial electrical grid specifically mentioned the replacement of “coal,” which has a reputation of being a particularly “dirty” energy source. Similarly, the other question referred specifically to the use of SMRs in “remote” communities without further definition, leaving respondents to draw their own conclusions on its meaning. For these reasons, further investigation of more general agreement with the use of SMRs in Saskatchewan would be valuable, as would a more expansive public dialogue. Nevertheless, the C-Dem and Viewpoint surveys clearly indicate that SMRs currently enjoy widespread support across the Saskatchewan public.

Methodology of the C-Dem Saskatchewan Provincial Election Study

The Saskatchewan Provincial Election Study was a two-wave survey conducted with an online panel. The Campaign Period Survey (CPS) was conducted October 14th 2020 to October 25th 2020. The survey was deployed online to a sample provided by the Leger Opinion panel (55%), Dynata (21%), and MaruBlue (24%). Leger coordinates the survey with an online panel system that targets registered panelists that meet the demographic criteria for the survey. Dynata provides a panel sourced from different channels delivering different populations to increase diversity and representativeness. MaruBlue provides a diverse panel actively recruited through online and offline methods. The sample was created by taking into consideration the response rates by age category and the quotas that were needed to achieve a representative sample based on age and gender. Survey data for the CPS is based on 1003 complete responses, all of which were valid. The C-Dem Saskatchewan CPS Survey was led by co-principal investigators Loleen Berdahl, Laura Stephenson, and Allison Harell. The Consortium on Electoral Democracy, co-directed by Laura Stephenson and Allison Harell, is funded by the Social Science and Humanities Research Partnership Grant (#895-2019-1022).

Methodology of the Viewpoint Saskatchewan Survey

The Viewpoint Saskatchewan Survey was conducted between March 1 to 10, 2021. The survey was deployed online by the Leger. A copy of the survey questions can be found here: http://bit.ly/30VcYEY. Leger co-ordinates the survey with an online panel system that targets registered panelists that meet the demographic criteria for the survey. Survey data is based on 800 responses, all of which were valid, with a 17-minute average completion time. The Viewpoint Saskatchewan Survey was led by co-principal investigators Loleen Berdahl and Jared Wesley. It was funded in part by a Kule Research Cluster Grant and an Alberta-Saskatchewan Research Collaboration Grant from the Kule Institute for Advanced Study (KIAS) at the University of Alberta and the College of Arts and Science at the University of Saskatchewan.

Endnotes

i. Hurlbert, Margot, and Dale Eisler. “Small Modular Nuclear Reactors in Saskatchewan’s Future?” Johnson Shoyama Graduate School Research Publications, November 2, 2020. https://www.schoolofpublicpolicy.sk.ca/research/ publications/policy-brief/are-small-modular-nuclear-reactors-in-saskatchewans-future.php.

ii. “Government Announces Strategic Direction on Uranium Development.” Government of Saskatchewan, December 17, 2009. https://www.saskatchewan.ca/government/news-and-media/2009/december/17/government-announces-strategic direction-on-uranium-development.

iii. Innovative Research Group. “2012 Public Opinion Research: National Nuclear Attitude Survey.” Canadian Nuclear Association, June 9, 2012. https://cna.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/2012-Public-Opinion-Research-%E2%80%93- National-Nuclear-Attitude-Survey.pdf.

iv. Canadian Nuclear Association. “Climate change considered the most extreme issue Canada currently faces despite unprecedented economic and employment uncertainties due to pandemic, reveals a new study.” Cision Newswire, September 2, 2020. https://www.newswire.ca/news-releases/climate-change-considered-the-most-extreme-issue-canada currently-faces-despite-unprecedented-economic-and-employment-uncertainties-due-to-pandemic-reveals-a-new-study 843045267.html.

v. Thoma, Jennifer. “U of S survey reveals Saskatchewan attitudes towards nuclear issues.” University of Saskatchewan Research Publications, May 12, 2014. https://news.usask.ca/media-release-pages/2014/10078.php. vi Hurlbert and Eisler, “Small Modular Nuclear Reactors in Saskatchewan’s Future?” 2020.